As comedian Rodney Dangerfield used to say: “I don't get no respect”!

Forgive the double negative, but farmers and supporters of our lowly alfalfa and grass crops seem like they have the same complaint.

Consider a few basic facts:

- Hay (especially alfalfa) is the third highest crop in economic return to farmers in the USA, behind only corn and soybean, worth $18-22 billion/year over the past 5 years (greater than wheat, cotton, rice, etc.)

- Over 2/3 of all agricultural land in the US is grassland with an economic value of $44 billion/year (2008, Sanderson et al., 2012).

- The forage-livestock food producing system, taken as a whole, is unquestionably the largest economic agricultural sector in the US and feeds millions of people each day.

- Forages contribute greatly to soil health, improved water quality, rotation benefits, wildlife habitat and have numerous ecosystem benefits

Forages such as alfalfa and grassy hay and pasture crops protect water quality, protect soils, and provide aesthetic value to the landscape, such as to this farming community in upper New York State. The presence of forages to filter water also helps to provide clean water to urban areas, such as New York City.

Where's the respect? Yet forages are the ‘Rodney Dangerfield' of crops – they don't get respect! Not only are forages not recognized by the general public for their economic and environmental value, but support for research is minuscule compared with other crops.

This is a problem begging the question: Will the general public, research community, and the farming community eventually recognize the importance of forage, pasture, and range crops, or allow this important sector to languish into the future due to lack of attention?

Recently, a large batch of forage agronomists (Cherney et al., 2018) from across the US put forward the following analysis that was recently published in Progressive Forage magazine.

Here are a few key points:

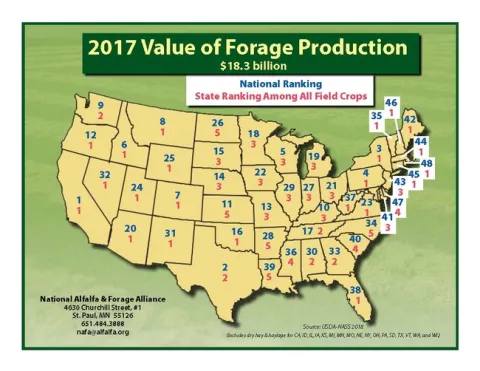

A little history: Forage crops are a major part of agricultural history going back thousands of years. Forage systems enjoyed maximum popularity in the US in the middle of the 20th century after the Dust Bowl era, with pastures and hay fields recognized for their soil conservation benefits. As the US population transitioned from rural to urban/suburban, federal and state support for agricultural research declined. The precipitous decline in support for forage crop research is strongly correlated with the power of commodity organizations and the perception of the commodity by the agricultural sector and the public. However, forages remain vitally important across the US (Figure 1), occupying a high spot in value and acreage in many states. Yet forages generally lack any commodity status and are perceived to be the least relevant when cuts to university research and extension programs and faculty are mandated.

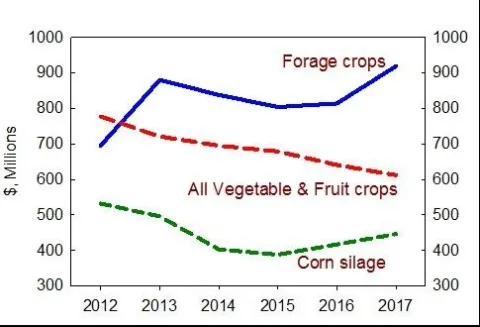

Are forage crops valuable? Yes! Alfalfa is the third largest crop in economic on-farm value currently, and ‘grasslands' have an economic value approaching $50 billion (Sanderson et al. indicates $44 billion in 2008)! Forages are vitally important to millions of farming enterprises as part of rotation or primary production. Forage crops can provide a minimum of 40%, and up to 100% of the total feed requirements of ruminants and serve as one of the primary resources that allow effective nutrient management planning. Ruminant agriculture (Cattle and Calves, and Dairy), provided greater than $110 billion/year ($112B, 2012 NASS stats) in value over the past 5 years, and plentiful forages (alfalfa, grasses, silages, rangeland) are the basis for their production. Perennial forages are frequently grown on land not suited to row crops and contribute greatly to domestic food security. Forages have increase in value in New York (Figure 3), and even in the super-charged specialty crop economy of California, alfalfa holds its own. Hay is worth over $1.3 billion in California and supports the >$7 billion/year dairy industry. Specialty crop growers of lettuce, onions, tomato and broccoli highly value the rotation effects of alfalfa, which is not only profitable in its own right, but contribute nitrogen and soil ‘tilth' (quality) to the next crop.

Figure 1. Value of US forage crops (hay and haylage only, not including extensive pasture, grasslands and rangelands), and ranking among field crops (corn, soy, cotton, wheat, etc.). Source: USDA-NASS. Map: NAFA.

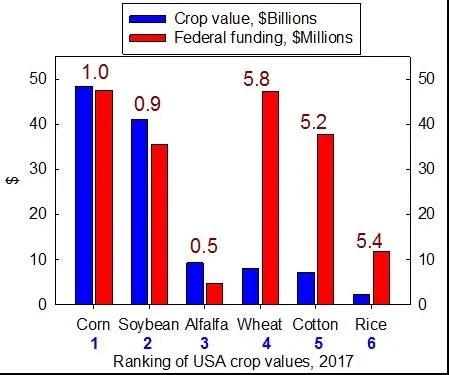

Does the Government Recognize this? No. The website of the USDA Economic Research Service highlights economically important US crops, and was updated May 8, 2018 (https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/). The list of “Crops” includes: Corn, Soybeans, Wheat, Cotton, Rice, Vegetables & Pulses, Fruit & Tree Nuts, and Sugar & Sweeteners (corn again). The first five crops listed here are often considered the “Big 5” in the country. Alfalfa and other forages are not considered economically important and are not mentioned, even though their footprint exceeds many of these.

High Economic Value, yet Paltry Research Support. USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) recently released 2017 field crop values, showing that alfalfa is now the third most valuable field crop produced in the USA (Figure 2). It is also clear from the figure that research funding for alfalfa is pitiful, compared to other crops. The #1 crop in the country, corn, is valued at almost five times the value of alfalfa, but has over 10 times the research funding (Figure 2). In New York state, forages have increased in value over the past 6 years (Figure 3). In 2017, alfalfa moved ahead of wheat in crop value, and while the wheat crop is valued at $1.2 billion less than alfalfa, it also receives 10 times more research funding as alfalfa.

Does the Public Recognize the Value of Forage Crops to the Environment? Probably not. Food production isn't the only value of forages. Increasingly, farmers are under the microscope for their environmental stewardship. The ‘ecosystem services' of forages are many and profound: These include improving air and water quality, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, nutrient and energy cycling, and species biodiversity and beneficial functioning of rural ecosystems (Sanderson et al., 2012; Putnam et al., 2001). Nitrogen fixation by forage legumes alleviates the environmental costs of nitrogen fertilizer production, transport and application. Perennial forages make a tremendous contribution to soil health, but are rarely credited for it. Alfalfa and pasture crops have tremendous wildlife value, which has been characterized by Audubon and other nature-loving groups, and summarized in a publication Alfalfa, Wildlife and the Environment (Putnam et al., 2001).

A little-appreciated value of forages is the value to wildlife habitat, as illustrated by this group of stags in northern California alfalfa field. A wide range of species utilize alfalfa and forage crops. These illustrate the ‘ecosystem services' provide by forage crops. See: “Alfalfa, Wildlife, and the Environment” publication and Sanderson et al., 2012.

Forages improve water quality. The New York City watershed in upstate New York provides drinking water for approximately 9 million people in the New York City area. This is the largest unfiltered drinking water supply in the USA. This high quality water does not require treatment, in large part, due to the strategically placed perennial forage crops grown on farms in the watershed, that protect the purity of the water supply (see photo). In California, Wisconsin, and many other regions, the use of grasses, well-managed pasture and rangeland and alfalfa as a ‘filter crops' protects water quality from nitrate and particulate contamination of surface waters.

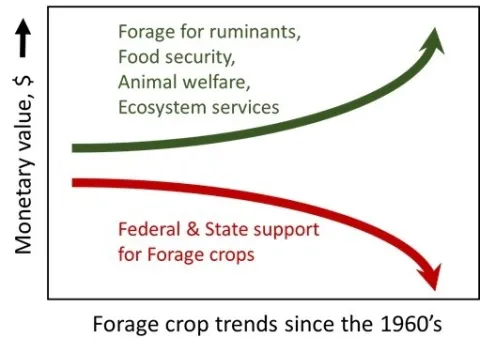

We've had a Large Reduction in Forage Teaching, Extension and Research. In spite of the importance of forage crops, we're losing expertise! All over the US,reduction in faculty appointments on forages have resulted in fewer forage courses and reduced development of future forage scientists. Over the last 20 years US forage research and extension scientists have decreased by more than 50%, with extension seeing the greater decrease. For example, approximately 70% of forage teaching, extension, and research faculty at Cornell University have been lost in the past 30 years. While the value of forages remains high or is increasing, we have seen a decline in research support (Figure 4). Because the value of forage crops is not appreciated by stakeholders, administrators and policy makers, extension positions are the least likely to be replaced when such positions become available. The farming community needs to draw attention to this.

Declining Support for Land-grant system as a Whole? Unfortunately, this decline in support for forages mirrors the decline in support for agricultural research as a whole.Land-grant programs have gradually become a casualty of their own success. Federal support for land-grant colleges has declined substantially during the past 40 years, forcing states to provide much of that support. In the increasingly urban states, particularly in the northern USA, and in the increasingly-urbanized West, competition from urban programs has claimed more tax revenues. Policy makers and stakeholders have lost touch with agricultural research and are less willing to support it. In witness of this fact, the urban public is much more willing to support crops that directly end up on their dinner plates, without considering the forages represented a wide range of important food products.

What have the Farmers Asked for? Research!

As important as forages are to farmers and to the farm economy, growers have never pushed for subsidies of any type (direct payments or other forms of subsidies) for forage crops, unlike commodity row crops which receive billions each year in subsidies. Forages are probably the closest to a ‘free market' crop as we have in agriculture. However, alfalfa growers, through grower associations (such as the National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA), the American Forage and Grasslands Council (AFGC), and state organizations such as the California Alfalfa & Forage Association (CAFA) have continually asked for increased funding for research for sustaining crop production for this important sector.

Modest Beginnings. A very tiny fraction of USDA-NIFA's research and education budget has been dedicated specifically to forage and grasslands (NIFA is a competitive grants program for agriculture). Recently, the National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA) convinced USDA to fund modest competitive grants program for alfalfa, which is now bearing fruit, and have generated a modest checkoff program of their own. USDA-ARS has also recently decided to put 2 forage scientists in California (after decades of neglect). We applaud these beginnings, but it is still clear that greater research investments in forages are needed. There are a wide range of pest management, forage quality, genetics, breeding, and whole-system management issues that need addressing.

What is the Consequence, a Forage-free future?

This discussion begs the question posed at the beginning of this article: Will the general public, the research infrastructure, and the farming community recognize the importance of forages or allow this important sector to languish due to lack of research support or attention? Given the erosion of expertise throughout the US, and the minuscule research attention given to this sector compared with other agricultural sectors, it is a question very much in the air.

Note: Dan Putnam is Forage Agronomist at University of California, Davis, and Jerry Cherney is Agronomist and Professor at Cornell University, Ithacca, NY. Derived from an article from Cherney et al., 2018. published in Progressive Forage, 2018.

References:

Cherney, J. K.A. Albrecht (WI), M.T. Berti, M. Bohle (OR), S.C. Bosworth (VT), K.A. Cassida (MI), W.J. Cox (NY), E. Creech (UT), S.C. Fransen (WA), M.H. Hall (PA), D.B. Hannaway (OR), M.A. Islam (WY), K.D. Johnson (IN), J.W. MacAdam, E.C. Meccage, D.H. Putnam, E.B. Rayburn, C.C. Sheaffer (MN), G. Shewmaker (ID), J. Solomon, R.M. Sulc (OH), and J.J. Volenec (IN). 2018. Forage in crisis: Forage crops don't get no respect. Progressive Forage Magazine.

Putnam, D.H., M. Russelle, S. Orloff, J. Kuhn, L. Fitzhugh, L. Godfrey, A. Kiess, and R. Long. 2001. Alfalfa, Wildlife and the Enviornment. The Importance and Benefits of Alfalfa in the 21st Century. California Alfalfa & Forage Association. UC DAvis Alfalfa & FOrage Workgroup. http://agric.ucdavis.edu/files/242006.pdf

Sanderson, M.A., L. Jolley, and J.P. Dobrowolski. 2012. Pastureland and hayland in the USA: Land resources, conservation practices, and ecosystem services. pp. 27-40. In (C.J. Nelson, ed.) Conservation Outcomes from Pastureland and Hayland Practices, Assessment, Recommendations, and Knowledge Gaps. Allen Press, Lawrence, KS.

Fig. 2. National crop value and federal funding for research for the top 6 field crops in 2017. Values above bars are the ratio of funding ($M) to value ($B). USDA-NASS and USDA-ARS data.

Fig. 3. Value of forage crops, corn silage, and all vegetable and fruit crops combined, in New York State, 2012-2017. NASS began publishing the total value of forage only in 2012.

Fig. 4. The value of forage crops is steadily increasing, while public support for forage research, teaching, and extension is steadily decreasing.