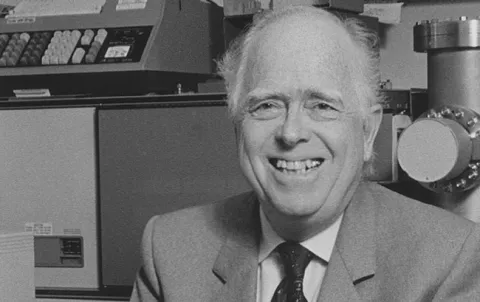

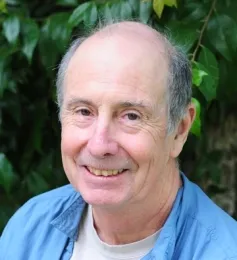

Casida, 88, one of the world's leading authority on how pesticides work and their effect on humans, died June 30 of a heart attack in his sleep at his home in Berkeley. He was considered the most preeminent pesticide toxicologist over at least the last two centuries.

A distinguished professor emeritus of environmental science, policy and management and of nutritional sciences and toxicology, Casida was the founding director of the campus's Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology Laboratory.

When awarded the Wolf Prize in Agriculture in 1993, the Wolf Foundation lauded his “research on the mode of action of insecticides as a basis for the evaluation of the risks and benefits of pesticides and toxicants, essential to the development of safer, more effective pesticides for agricultural use." according to a UC Berkeley News Service story. "His discoveries span much of the history of organic pesticides and account for several of the fundamental breakthroughs in the fields of entomology, neurobiology, toxicology and biochemistry.”

Former graduate student Bruce Hammock, now a distinguished professor at the University of California, Davis, who holds a joint appointment with the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology and the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, remembers him as a “lifelong mentor who evolved into a colleague and a friend.”

“John continued his high productivity until his death with major reviews on pesticides in 2016, 2017, and 2018 in addition to numerous primary papers,” Hammock noted. “He was working on primary publications as well as revising his toxicology course for the fall semester at the time of his death. Pesticide science was the theme of his career, and we live in a world with far safer and more effective pest control agents because of his effort.”

John Casida opened multiple new fields ranging from fundamental cell biology through pharmaceutical discovery. "He pioneered new technologies throughout his career, from being one of the first to use radioactive compounds for pesticide metabolism through studies with accelerator mass spectrometry, photoaffinity labeling and others," Hammock related. "Yet the greatest impact of his career probably lives on in the numerous scientists he trained, now carrying on his traditions of excellence in science. These scientists are around the world in governmental, industrial and academic careers.”

As compiled and shared by Hammock, below are comments from a few of his doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows who worked both with Casida at UC Berkeley and at, least for a time, also were at UC Davis.

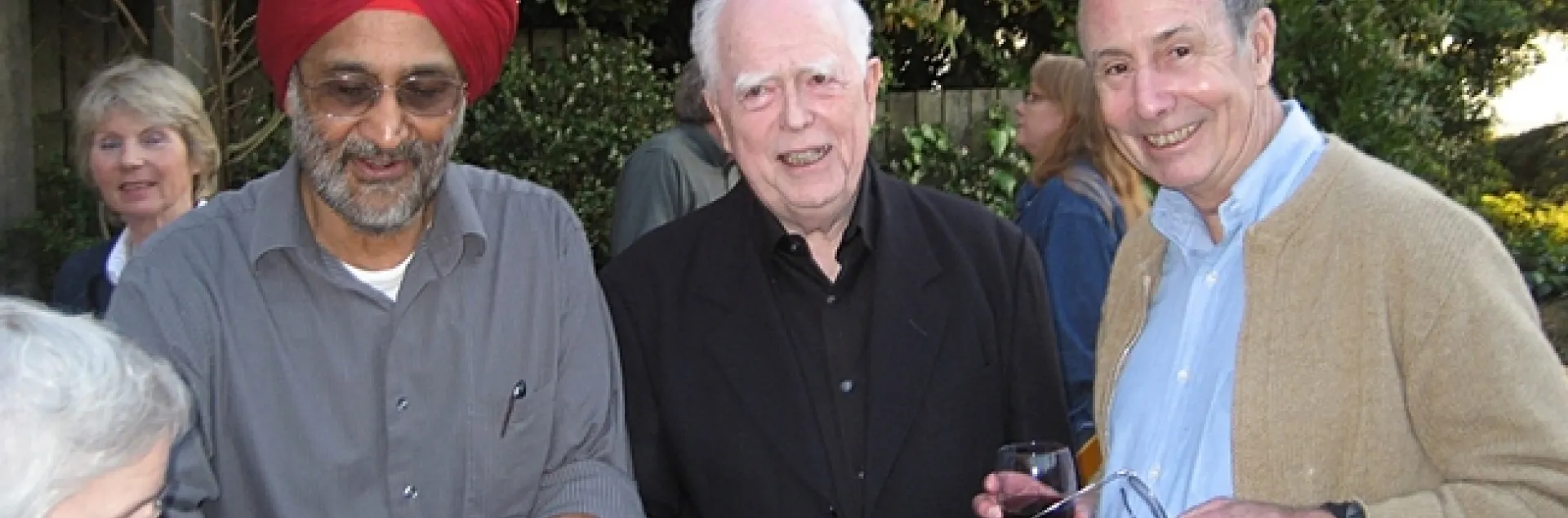

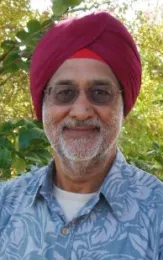

Sarjeet Gill

Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, University of California, Riverside

"This project also allowed me to build a long lasting friendship with Bruce Hammock who also was on the same project. Since John was always very focused, I often challenged John's patience with my practical jokes. I am sure he knew who the culprit(s) were but he never revealed he knew.

“The research experiences in John's lab made an indelible impression on me that drove me to return to the United States from Malaysia for an academic career in the UC system. Personally, I have lost an incredible mentor, and the scientific community lost the most preeminent pesticide toxicologist in the last two centuries. John changed the way we investigated mechanisms of toxicity at all levels. I certainly will miss him dearly.

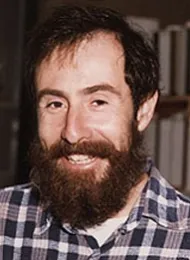

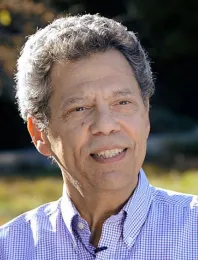

Bruce Hammock

Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Davis: Joint appointment with the Department of Entomology and Nematology and the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

"After telling him I was there to be his graduate student, he replied he had no money for students. My retort was that I had a fellowship. He then told me that students were not space effective, and I promised not to take up much space. He continued that students were not time effective, and I promised not to take his time. In retrospect, Sarjeet must have really soured him on graduate students a few hours earlier."

"Months later, Sarjeet and I were sharing a desk-lab bench in the windowless closet next to the 'fly room' when Dr. Casida walked in. He had noted we both listed him as our major professor and asked if there was anything, he could do to encourage us to leave. When in unison we replied 'No!,' he politely left without accepting us, but soon we both had a desk and bench.

"So a few paces after Sarjeet, I initiated the most thrilling four years of my life. John's introduction to experimental science was marvelous with the perfect balance of inspiration, instruction and tremendous freedom. I was privileged to learn from a wonderful group of individuals and, of course, I made my most enduring of friendships with Sarjeet Gill. In addition to science, John taught a life-family-science balance by example. John was my life long mentor in science and in life but also evolved as a colleague and friend.

"Three more delightful years passed and John then took me to lunch at the faculty club. As I was about to leave the laboratory for the U.S. Army, he gave me sagely advice such as he had had it easy during the Sputnik period and I would have it hard. Then he went on to tell me than most people in the laboratory did not find my practical jokes nearly as funny as I did. I did not reveal that Sarjeet had both planned and executed most of them. Thus, Sarjeet succeeded in disrupting my Berkeley career from beginning until the end.

"John and his laboratory at Berkeley provided me with the most exciting years of my scientific career. In his own work, John moved from strength to strength creating numerous entire fields along the way. His scientific insight and drive were a constant stimulation to drive for innovation and excellence. Whenever I had an opportunity, I encouraged others to join his team. John was an inspiration and role model, not only because John came in early and stayed late, but also because he did science for the fun of discovery and taught for the joy of teaching."

Keith Wing Consulting LLC

Life Science Industrial Biochemistry or Biotechnology

"While we all worked hard including many evenings and weekends, there were times when I or other American rebels would lead a mass lab exodus for a salmon fishing or ski trip during (gasp!) regular business hours. John would pretend to barely notice our ill-disguised escape along the cabinets that lined the Wellman Hall basement, except to raise his right eye from his manuscript editing in an unmistakable sign of disapproval at our lack of scientific drive.

"And this leads to another Casida work pattern of the time…. All of us scientists were subject to John's multiple cycles of manuscript editing. We would wrack our brains trying to put the right words and figures down as manuscript drafts, submit them to John, and wait for three days or less for him to return it to us in a sea of thin red ink, and the humbling realization that we really were much poorer writers than we'd thought. After discussion with John and acquiescing to practically every edit he'd made, the manuscript would be re-typed manually by his administrative assistants in entirety and the cycle would repeat but with less red ink. After at least three cycles of this, we'd submit the manuscript for publication, often with a high acceptance rate. With time, we all came to understand and see John's wisdom in approaching publication and science contribution. All of this occurred right as word processing programs had started taking hold in the outside world, and perhaps my one service to the lab on my 1983 exit was to convince John to look into using word processing/saving documents on disks for editing. Oh, and maybe a bit of science as well.

"John Casida's lab has been the world leader in examining both pesticide metabolism and their biochemical target sites. I was lucky enough to work on a project that combined both, and it molded the way I looked at insecticide discovery in industry. The interdisciplinary approach to the mechanisms by which xenobiotics interface with biological systems influenced the thinking of every person who has passed through John's lab. That influence has proliferated throughout the world and has advanced the field of pesticide toxicology to what it is today. We mourn the loss of a great leader but understand that his alumni are a large international family that will carry his spirit and teachings forward."

Andrew 'Andy' Waterhouse

Director of the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science and Professor of Viticulture and Enology,

University of California, Davis

"A couple of weeks after I arrived, he showed me Don Crosby's book on natural toxicants, and asked if I would confirm the very high toxicity of ryanodine mentioned therein. The high toxicity suggested strong binding to a key regulatory protein, and its novel and unknown mode of action made it an exciting prospective target. Confirming that ryanodine was in fact a deadly toxic, he set a project in motion to discover the site of action, hiring Isaac Pessah to use the yet-to-be-made radioligand on a hypothetical site of action!

"We were astonishingly lucky to find that the natural source of ryanodine contained a major impurity that was one step away from the highly radioactive form, so it wasn't too long before we had very hot ryanodine available. Initial attempts detected no binding at all, but Isaac thought to add some calcium to the assay, and we had the binding site in hand! This discovery essentially established a field of science in muscle physiology and pharmacology, with entire symposia dedicated to exploring this binding site and its broader significance to toxic modes of action. Isaac is an established leader in the field. It was a real privilege to see how groundbreaking research can happen and be part of it, and to get to know all the fabulous scientists that John collected around him."

Isaac Pessah

Associate Dean of Research and Graduate Education, and Professor, Department of Molecular Biosciences, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

University of California, Davis

"I remember most vividly my reaction when John also indicated that working on the biochemistry GABA receptors, my original intent for traveling across country for a postdoc, was not to be. ‘Work on something else' John advised, ‘there are so many interesting unanswered questions around the PCTL.' Arguably John's straightforward and highly insightful advice changed the course of my professional life. He introduced me to chemist Andy Waterhouse, and the next two years of work that led to the discovery and identity of the ryanodine receptor were breathtaking. Our discovery benefited from many factors; a gift from Ryania speciosa in the form of didehydroryanodine, which Andy identified, the newly published use of palladium catalyst to catalyze efficient reduction of minute quantities of unsaturated bonds, the National Tritium Laboratory just above the PCTL…and of course, there was John's unwavering support for discovery, no matter how risky. Successful synthesis of [3H]ryanodine and identity of its receptor paved the way to immense basic discoveries in virtually every field of science, identification of several disease causing mutations of skeletal and cardiac muscle and the nervous system, and successful discovery of highly selective ryanoid insecticides. Since the first paper published in 1985, there have been nearly 20,000 peer reviewed publications (ISI Web of Science) and a search on Google Scholar yields more than 70,000 hits. To many, John was the recognized leader in pesticide chemistry and toxicology. I agree, although from my perspective, John was also a true renaissance individual, seeding ideas of great significance in so many fields, of which ryanodine receptors represents only one of many. His love of science and discovery positively impacted his students and postdocs. He will be fondly remembered and sorely missed.'

Qing Li

Professor, Department of Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa

" In April 2018, I had a couple of telephone conversations with Professor Casida. He shared with me what he was doing (of course, writing manuscripts), his health, Kati's health, his sons and his grandkids. We talked about meeting at the Biochemistry and Society: Celebrating the Career of Professor Bruce Hammock, to be held in Davis in August 2018. We talked about a possibility to attend a meeting together in China in 2019.

"I was privileged to manage Professor Casida's manuscript entitled 'Pesticide Detox by Design' that he submitted to the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. This is Professor Casida's last manuscript, I believe. It is still in the review process. He wrote that 'Detoxification (detox) plays a major role in pesticide action and resistance…' A reviewer who reviewed the manuscript wrote me “I just heard that Professor Casida has passed away... Professor Casida was a giant in pesticide science, a special and unique person. It is a great loss to the pesticide science community…”

Professor Casida is survived by his wife, artist and sculptor Kati Casida, sons Mark and Eric Casida, and two grandchildren.

Related Information

- John Casida Obituary, UC Berkeley News Service

- For the Fun of Science: A Discussion with John E. Casida (Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology)

- ?Still Curious: An Overview of John Casida's Contributions to Agrochemical Research (JAFC)

- ?Curious about Pesticide Action, by John E. Casida (JAFC)