From one small town to another, REC director inspires youngsters to consider careers in agriculture

In celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month

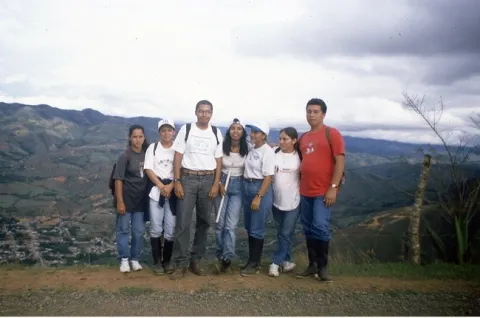

In the small town of Buga, located in Valle del Cauca in southwestern Colombia, Jairo Diaz-Ramirez prioritized salsa dancing over his studies. His parents, noticing that he was having too much fun on weekends, reminded Diaz that schoolwork comes first. “I used to dance a lot and spend time with friends when I was a teenager, and I didn't pay full attention to schoolwork,” he said.

Diaz, director of the UC Desert Research and Extension Center – one of nine centers under University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources – located in Holtville, was born and raised in Colombia, where the life of a farmworker was all too familiar.

Before Diaz's father joined the army, he worked in the fields. Describing his father as an “autodidactic person,” Diaz said that his father acquired many skills throughout his life and could “fix pretty much everything.” Others knew this about Diaz's father, often referring to him as “el cientifico” or the scientist.

“My hometown is surrounded by agriculture, and I saw farmworkers all the time. What they do is difficult work, it's hard,” he said. Even though Diaz has a career in agriculture today, he did his best to avoid it when he was in school.

In high school, Diaz focused on math and science, believing it would lead him down a different career path. When he graduated in 1990, Diaz didn't have many options for a college education in his area. “There was barely internet in my hometown,” he recalled, adding that it was a challenge to find professional mentors, too.

“I didn't know what I wanted to study,” said Diaz. “But when I passed the entry test for college, I just decided on electrical engineering.” As a freshman in college, Diaz found himself in a different environment with rules and expectations he was not used to. “I lost focus,” he said.

In fact, his poor academic performance led Diaz to drop out of college. He described this decision as, “the inflection point that changed the course of his life.” Realizing that he took a great opportunity for granted, Diaz wanted to return to school. After passing the college entry exam a second time, his test results matched him to the following career options: agricultural, sanitary or chemical engineering.

Because it required fewer chemistry courses, Diaz decided to pursue agricultural engineering. The more he learned, the more interested he became in irrigation, watershed management, soil and water conservation. In 1997, he obtained a bachelor's degree in agricultural engineering from National University of Colombia and University of Valle.

Realizing there's more to agriculture

There was a shift in perspective that occurred for Diaz, one that made him see other pathways into agriculture other than farm labor.

“I always saw the workers in the field from four in the morning to six at night, even on Saturdays,” Diaz said. “But I never saw what was behind agriculture. Labor is one thing, but there's also the science, education, management, engineering… I didn't see that when I was younger.”

In 2001, after two years of working as a part-time instructor at community colleges in his hometown, Diaz moved to Puerto Rico, where he earned a master's degree in water resources engineering from University of Puerto Rico. Although he would have liked to attend graduate school in his home country, career opportunities were limited.

“I considered schools in Spain and Chile, somewhere the people speak Spanish,” said Diaz, sharing that the ability to learn in Spanish was his preference.

Meeting students halfway

Eventually, Diaz moved to Mississippi, earning a doctorate in water resources engineering at Mississippi State University before he began teaching at Alcorn State University – the oldest public historically Black land-grant institution in the nation – where his role as a mentor easily became his favorite part of that journey.

As an assistant professor, Diaz said that many students he worked with at Alcorn State struggled with higher level courses of agriculture. “Some of my students started with me when they were freshmen and I got to see them progress over the years,” said Diaz.

Now, many of them work for the federal government and non-governmental organizations, and some have even moved to other states, away from everything and everyone they know.

“It reminds me of my own people,” Diaz said. “How challenging education can be, and how limited you feel, and being afraid to move away from home…that's what many of us BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, people of color] experience.”

Once a mentor, always a mentor

In Imperial County, where Diaz currently lives, more than 80% of the population is Hispanic. According to Diaz, many of the students in Imperial can relate to those he taught in Colombia, Puerto Rico and Mississippi, struggling to navigate education. “A lot of the students also think like me when I was their age. They don't find agriculture appealing because it's too hard.”

That's where Diaz steps in and shows them a different side of agriculture, one that he wishes someone would have shown him when he was younger. When he visits local schools, or hosts student groups at Desert REC, he teaches students that agriculture offers a broad spectrum of opportunities.

“Agriculture is not just about people in the fields, it's people in the labs, at the computers and in the classroom. It's people managing others, figuring out economics and building systems,” he said.

Given his background in hydrology, irrigation systems and water resources, Diaz relies on water as the element to engage students in conversations about agricultural careers. “To produce food, we need water. Plants need water to live and so do we. Water is key,” he tells students.

“I know how much of a difference it makes to have someone guide you professionally. So, I want to be that person for my community, especially the younger generation.”

As a director, Diaz has an open-door policy to encourage frequent interactions with his colleagues. “It's important to me that the people I work with know that I want to support them,” said Diaz, who prefers colleagues call him by his first name.

“Sometimes you hear that someone is a ‘doctor,' and it creates a divide right away,” he said.

While reflecting on his role and impact, Diaz said that he wants to be known as a genuinely good person. “I want to be a good collaborator, create meaningful programs, and grow a healthy industry.”

These days, Diaz doesn't spend much time on the dance floor, but he won't shy away from an opportunity to relive his adolescence. “I have created my own career path with the support of my family, mentors and friends,” he said. “I still have fun, but I also focus when I need to.”

To watch a past feature on Diaz in celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ksNc7qDCOVo.

To read this article in Spanish, visit: https://espanol.ucanr.edu/Abriendo_Caminos/?blogpost=58085&blogasset=139086.